Extracts from the book – The Valley of Flowers

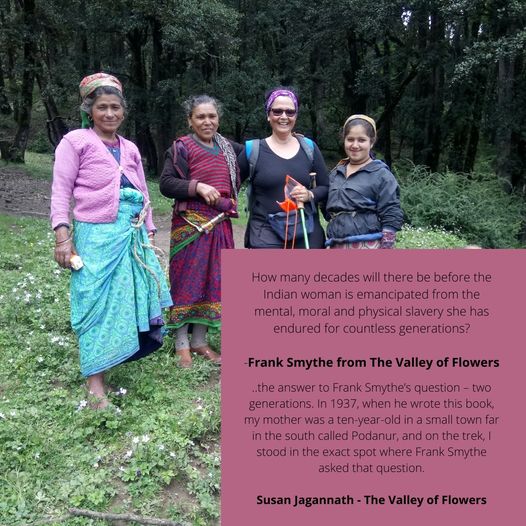

How many decades will there be before the Indian woman is emancipated from the mental, moral and physical slavery she has endured for countless generations?

-Frank Smythe

In the beginning there was a quiet valley, veiled in cloud and wreathed in glaciers and utterly remote from the teeming masses of the plains. But then one day it welcomed a lost wanderer stumbling out of a Himalayan storm, and it became known as the Valley of Flowers to the world.

The people of the mountain, the simple shepherds had long known this valley as Nandan Kanan, the last verdant valley before the brown dry hills of Tibet that lay in the rain shadow of the mighty Himalayas. And year after year it lay quiet and forgotten, except by a few intrepid souls ready to walk for days to reach it.

And when we knew of it, it was like a dream hovering in the distant north. In the vibrant south of India, we got on with converting the sleepy retirement town of Bangalore to the IT capital of the world, and building careers that as Indian women, not even our mothers could have dreamed of.

And we, the answer to Frank Smythe’s question – two generations. In 1937, when he wrote this book, my mother was a ten-year-old in a small town far in the south called Podanur, and on the trek, I stood in the exact spot where Frank Smythe asked that question.

Getting Real

It started as a conversation on Whatsapp across three continents

- When were we going to do that things we wanted to do?

- With the people we wanted to do it with.

It was already June, and the monsoon was late, it gave us an opportunity – we could walk the Valley of Flowers in early August or September. One by one, we go over the options; independently, or hiring our own taxi, walking on our own, pre-booking? There was no guidebook that we could consult, so we throw our search net far and wide over the internet.

The options narrow as we realize we have limited time; we cannot wait around to catch buses or shared taxis, and I’m always carsick on mountain roads. We need our own car and driver. And I need to sit in the front.

It later transpired that the roads are so precipitous and wet, and the curves so continuous and convoluted, that I sit one row back in the car, but that’s another story.

Once we have our dates and times down, it’s time to plan. We have a ten-day window in which to do a three-day trek, that sounds easy. Until we realize that we need to get to the valley, and acclimatize at heights. I have no qualms about admitting that I have altitude sickness, so we need a slow climb up to the start of the Valley of Flowers. And that needs some negotiation, as the tour operator wanted us in and out fast, and we didn’t. We hand over all the decisions to the best planner among us, Anju takes it all over, and we mostly just nod and smile as she does a great job. I smile to myself as I think back to the time ages ago at work, where I mistook her for someone’s little sister, not a key developer on India’s first supercomputer.

And when we knew of it, it was like a dream hovering in the distant north. In the vibrant south of India, we got on with converting the sleepy retirement town of Bangalore to the IT capital of the world, and building careers that as Indian women, not even our mothers could have dreamed of.

And we, the answer to Frank Smythe’s question – two generations. In 1937, when he wrote this book, my mother was a ten-year-old in a small town far in the south called Podanur, and on the trek, I stood in the exact spot where Frank Smythe asked that question. Here is the picture of the position, from a careful reading of his book that is the same spot. And here I am, with a group of pahadi woman who were herding a cow and calf up to their summer meadow.